Data analysis exercise:

COVID-19 in México

Abstract

COVID-19 reached every place on the earth. An examination of open data from México will reveal the situation there. This paper aims to describe it by showing plenty of plots and graphs, explaining how to develop them in the process. The purpose, to strengthen my general analysis skills, practicing methods used to produce high-quality materials like this web page and the media displayed in it.

Seven minutes read.

Regarding the data

The CSV$ ^1 $ was uploaded by José Héctor Paredes Martínez, Epidemiological Notification and Registry Director of the Secretaría de Salud at Mexico’s government. Composed of 12,133,530 lines, the database contains a variety of information like death dates, gender, whether intubation was required, nationality, and more input which help get an idea of the situation in México. I manipulated the material with Wolfram Mathematica 13.0.0, fragmenting the rows with the rust crate, split-csv, into 101 smaller documents for easier processing.

It’s necessary to divide the 2 GB single archive, since trying to import all 12 million registers at once into a dataset fails after more than 30 minutes because of massive virtual memory space required. By splitting the contents, I gain speed and flexibility when coding due to low loading times and memory usage per file.

Counting

This first section visualizes basic information, counting the number of people that fulfills a condition.

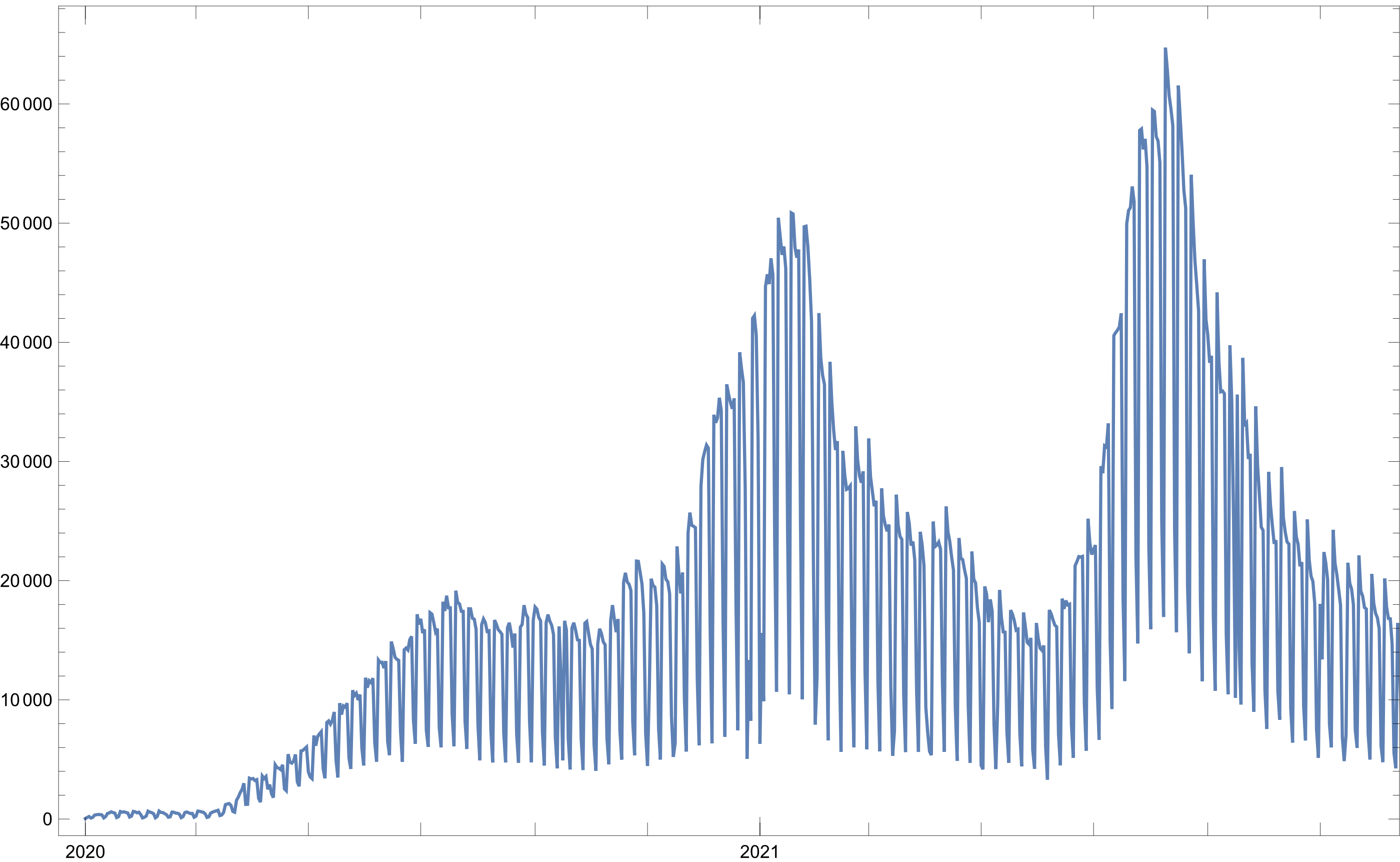

All-time attendants

All 12 million rows correspond to an individual visit to an attention unit. To get the evolution of entrance at health centers, we can use the following code.

result = <||>

Do[

file = "~/Downloads/covid/covid_"<>ToString@file<>".csv";

Print["Loading... "<>file];

data = Import[file, {"CSV", "Dataset"}, "HeaderLines"->1];

dates = Counts[Normal@data[All, "FECHA_INGRESO"]];

result = Merge[{result, dates}, Total],

{file, 1, 101}]

dates = Flatten /@ List @@@ Normal @ result;

Do[dates[[n]][[1]] = FromDateString[dates[[n]][[1]]], {n, 1, Length[dates]}];

Dplot[dates]

Overall, it plots an association that packs the engineered data for each file.

Achieved by creating an empty association filled with the outcomes of a process that is executed $ n $ times when $ n $ is the quantity of archives with the CSV form.

The process formats $ n $ with a hardcoded path to open a file and load it into a dataset.

To prepare the information, it declares a list containing the values of the column FECHA_INGRESO, counts the number of occurrences of the values, stores the result to date and, using Merge with Total , appends dates to results, merging the new dates as new keys or adding their values for already existing keys.

Finally, it transforms the association into a matrix of two columns, formatting the dates, for them to be objects instead of strings and be able to plot the matrix with the custom function Dplot.

Figure 1: Daily people registration over time

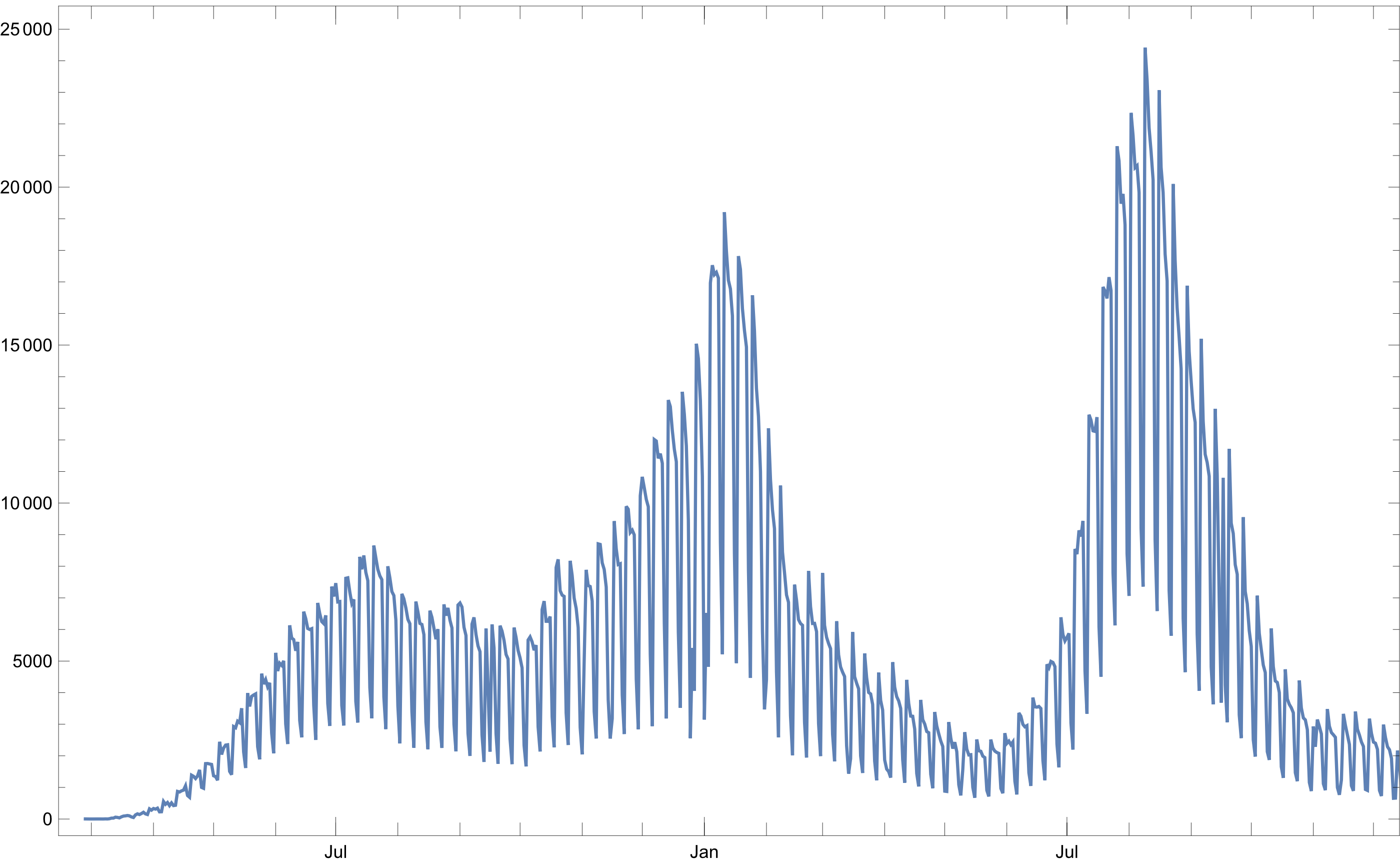

Confirmed cases

By implementing an algorithm almost identical to the first one, but changing the target column, we can get the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, using a custom function, ** PerformForEach**, to avoid some boilerplate to open and manage each cdv file:

PerformForEach["~/Downloads/covid", <|

Pre -> ((

result = <| |>;

)&),

Code -> ((

datesCovid = Counts[

Normal@#Data[Select[#"CLASIFICACION_FINAL" == 3 &], "FECHA_INGRESO"]

];

result = Merge[{result, datesCovid}, Total];

)&),

Pos -> ((

datesCovid = Flatten /@ List @@@ Normal @ result;

Do[

datesCovid[[n]][[1]] = FromDateString[datesCovid[[n]][[1]]],

{n, 1, Length[datesCovid]}

];

Print@Dplot[datesCovid];

)&)

|>];

Figure 2: Confirmed COVID-19 cases over time

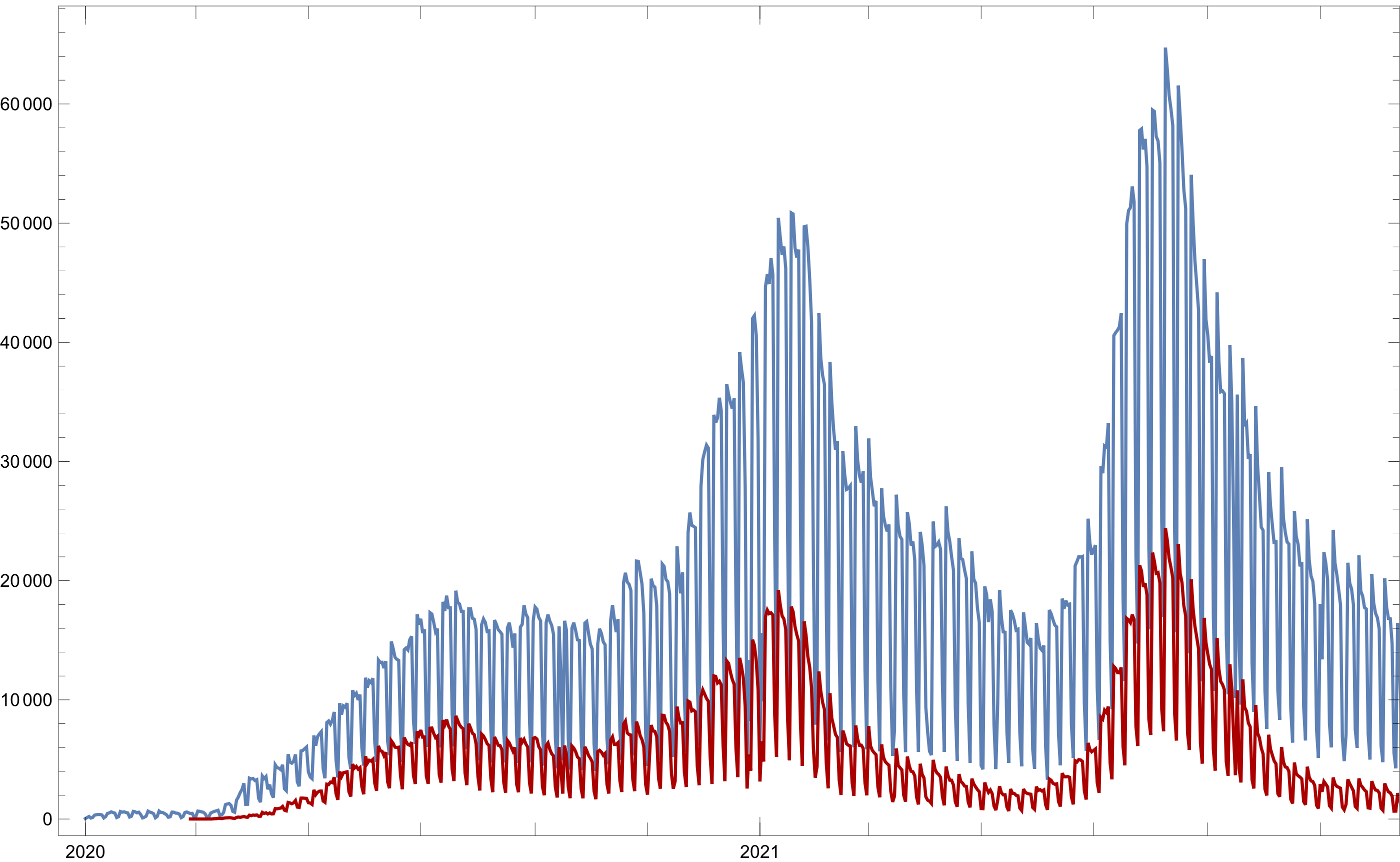

Confirmed vs. Total

To get a better understanding of what is happening on both plots it’s necessary to make a comparison of some sort between the graphics, the simplest form is to plot the two of them in a single-axis space. This can be managed by using Show.

Show[Dplot@dates, Dplot[datesCovid, PlotStyle->Darker@Red]]

Figure 3: Total attendance registration and confirmed cases per day over time

Taking a look at Figure 3, there appears to be a relation between the number of Mexicans attending sanity barracks and confirmed cases over time, which may evidence that COVID-19 “waves” are merely indicators of individuals presenting to treatment and diagnosis stations —maybe due to paranoia— and not because of the presence of actually a lot of infected.

With the purpose of getting a clearer idea of this last point, a method may be to view the percentage of people that tested positive for Covid of the 200% of people that attended a health center.

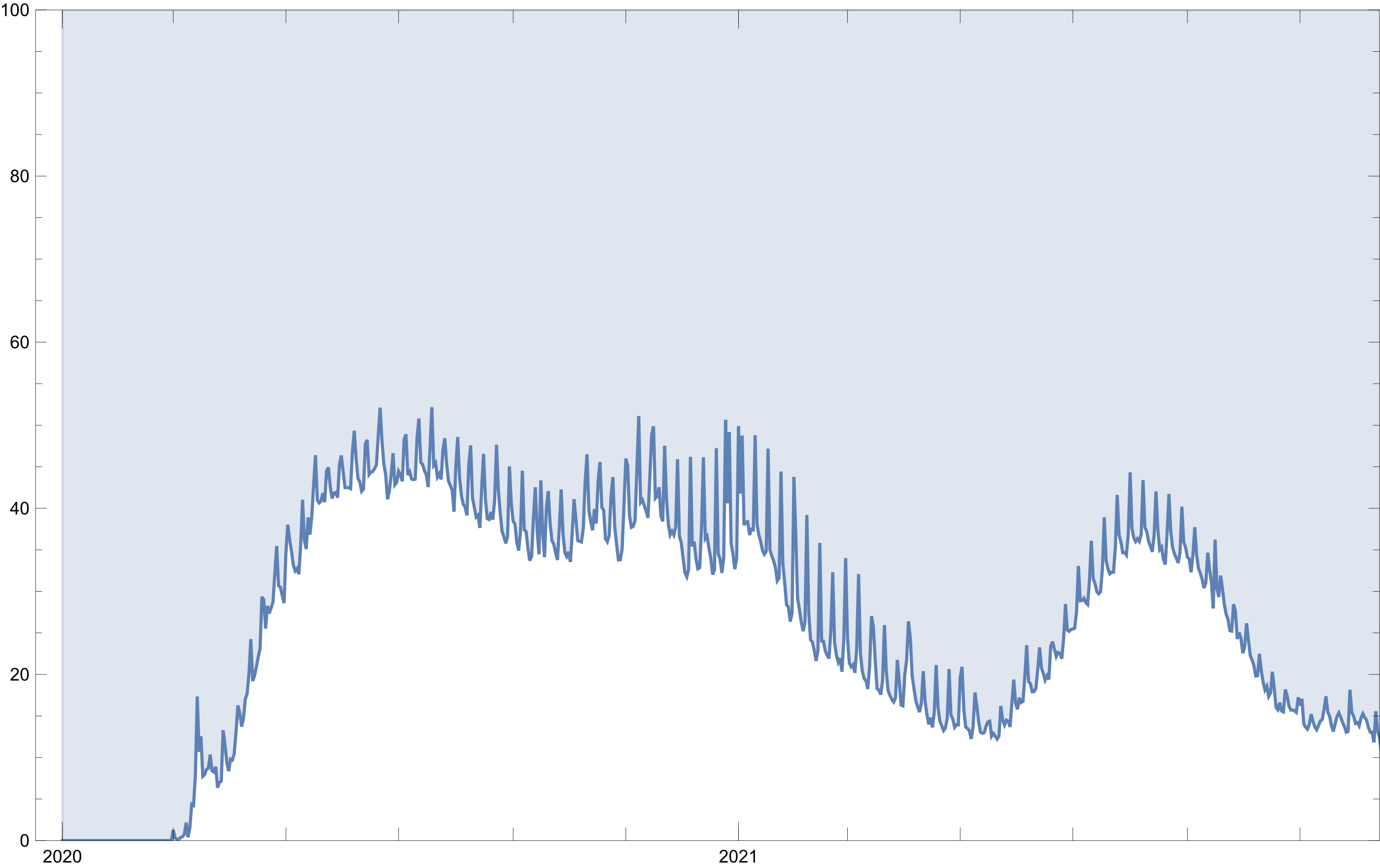

COVID-19 confirmed percent by day over time

To accomplish this, more code is needed. Since the arrays extracted from the dataset are disordered, it’s necessary to sort them by date, like DateListPlot does. Then prepend zero values to the collection for both to have the same length, and late divide each element of the raw total established cases by the complete number of people.

rawdatesqc = {};

Do[

AppendTo[rawdatesqc, e[[2]]],

{e, SortBy[datesCovid, AbsoluteTime[#[[1]]] &]}

];

rawdatesqc = PrependTo[rawdatesqc, Table[0, 31+29]];

rawdatesqc = Flatten[rawdatesqc];

Hence, first compile the patients with confirmed COVID-19, sorted by date and with some extra zeros at the beginning to match widths.

rawdatesq = {};

Do[AppendTo[rawdatesq, e[[2]]], {e, SortBy[dates, AbsoluteTime[#[[1]]] &]}];

Then we get the area of the number of people registered at an attendance center and fix by the day.

percentPerDate = {};

percents = N[rawdatesqc/rawdatesq * 100];

Do[percentPerDate = AppendTo[

percentPerDate,

{

SortBy[dates,

AbsoluteTime[#[[1]]] &][[i]][[1]],

percents[[i]]

}],

{i, 1, Length[rawdatesq]}

];

Finally, declare an array, populating it with the result of the division of confirmed by total of every index and prepend its corresponding day.

Dplot[percentPerDate, Filling->Top, YRange->{0,100}]

Figure 4: Percent of confirmed cases per number of registrations over time

From this perspective, there appears to be two COVID-19 waves instead of three as displayed in Figure 3.

Cases per Administrative Divisions

With a similar approach to the method used to count all confirmed cases, but with an extra check for the 32 entities of México. As an outcome, an association with 32 keys for each administrative division gained at the end of Code instead of a single result for the whole country.

PerformForEach["~/Downloads/covid", <|

Pre -> ((

result = <||>;

)&),

Code -> ((

Do[

entity = Counts[

Normal@#Data[Select[#"CLASIFICACION_FINAL" == 3 && #"ENTIDAD_UM" == en &],

"FECHA_INGRESO"]

];

If [ KeyExistsQ[result, en],

result[en] = Merge[{result[en], entity}, Total],

result[en] = entity

];

,{en, 1, 32}]

)&),

Pos -> ((

entity = <||>;

plots = {};

Do[

entity[en] = Flatten /@ List @@@ Normal @ result[en];

Do[

entity[en][[n]][[1]] = FromDateString[entity[en][[n]][[1]]],

{n, 1, Length[entity[en]]}

];

plots = AppendTo[plots, Dplot[entity[en]]];

,{en, 1, 32}]

)&)

|>];

Then, a sum of all cases can be computed for each entity.

Table[Sum[e[[2]], {e, entity[en]}], {en, 1, 32}]

Returning: {37876, 83146, 57416, 23697, 97912, 32851, 21214, 71485, 949633, 48989, 198388, 75604, 60673, 162487, 229096, 72058, 48098, 34019, 206653, 79510, 123996, 99596, 58782, 106373, 72865, 99407, 144732, 103770, 26673, 119370, 75034, 41756}

Result which can be utilized to generate various graphics. For example, employing the code within Figure 5, which uses a custom function, ** PieFromTotal**, whose prototype looks:

PieFromTotal[

totalN,

{quantity1, quantity2, ...},

{legend1q1, legendq2, ...},

Options

]

Which places the quantities inside a pie of size totalN and automatically calculates and displays each value’s percent.

PieFromTotal[

Sum[

k,

{

k,

Table[Sum[e[[2]], {e, entity[en]}], {en, 1, 32}]

}

],

Table[Sum[e[[2]], {e, entity[en]}], {en, 1, 32}],

estados,

ImageSize -> Full,

SectorOrigin -> {{Pi/12, "Counterclockwise"}, 1}

]

Figure 5: Custom code to generate a Pie Chart

The code displayed at Figure 5 generates the output:

Figure 6: Pie chart of total confirmed cases per administrative division

Figure 6 shows a disproportionate value that corresponds to Mexico City when compared to the reported values of the rest of the Mexico’s states. Figure 7 confirms this point.

The following code generated Figure 7.

RectangleChart[

{Table[{10, Sum[e[[2]], {e, entity[en]}]}, {en, 1, 32}]},

ChartLabels -> Placed[estados, Above],

ImageSize -> Full,

LabelStyle -> Directive[20]

]

Figure 7: Rectangle chart of total confirmed cases per administrative division

Percent of confirmed cases per state

An alternative, once again, is to generate a plot that displays percent of confirmed Covid cases per state based on the information that is displayed in Figure 8, generated by the code above it.

confirmed := Sum[e[[2]], {e, entity[en]}];

total := Sum[e[[2]], {e, entity2[en]}];

blue := RGB[113, 149, 199]

labels := ChartLabels-> Placed[estados, Before]

style := {BarOrigin->Left, LabelStyle->Directive[20]}

Show[{

RectangleChart[

{Table[{1, total }, {en, 1, 32}]},

labels,

style,

ChartStyle->blue

],

RectangleChart[

{Table[{1, confirmed}, {en, 1, 32}]},

style,

ChartStyle->Red

]

}, ImageSize->Full]

Figure 8: Total and confirmed cases per state

A very similar code generated Figure 9. From the perspective of the chart, according to the data, Mexico City is not the state with the worst ratio, it is Oaxaca is.

Figure 9: Percent of confirmed cases per state

The ratio probably does not display the real situation. Keep in mind that this data depends on the number of people that did visit a COVID-19 Stations, there are people that, even though they got symptoms, don’t go to the medic nor to attention units. As shown in a report from the México’s government, where it’s indicated that the optimal occupancy percentage is 90%, but the average of the county is approximately 76%, with places like Campeche with only 56.4%. I indeed do know many people who do not attend to health centers.

In general, a value between 85% and 90% is identified as the optimal level of the indicator. In 2014, the national occupancy percentage was 75.8% (…). The result obtained is close to 10 percentage points below the expected level.

(Informe sobre la Salud de los Mexicanos, 2016, p. 106)$ ^2 $

Whether people attend to hospitals or not is out of the scope of this writeup.

Sorting the percent of confirmed cases per state

Next, let’s sort the charts in Figure 9 with the following code:

sortedStates = SortBy[

Table[{en, confirmed/total * 100},

{en, 1, 32}],

( #[[2]] &)

]

In which we specify ( #[[2]] &) , hence, sort the matrix with the value in the second index of each list in the matrix.

Figure 10: Percent of confirmed cases per state, sorted from greatest to lowest

To sum

Mathematica is a great software where we can easily analyze huge amounts of data and produce high-quality and very flexible and personalized representations of the data with friendly standard functions and very few lines of code. I could keep on generating more figures from the data like those displayed in https://coronavirus.gob.mx, but I won’t because of time. Although, we do get an idea of how simple it is, at least with this example, to analyze, filter, sort, load and view big chunks of data.

References

- Martínez, J. (2020-08-06) "Información Referente a Casos Covid-19 En México". https://www.gob.mx/salud: Secretaría de Salud. Retrieved from datos.gob.mx on December 16, 2021.

- Secretaría de Salud. (2016). "Informe sobre la Salud de los Mexicanos 2016: Diagnóstico General del Sistema Nacional de Salud". Retrieved from www.gob.mx on January 7, 2022.